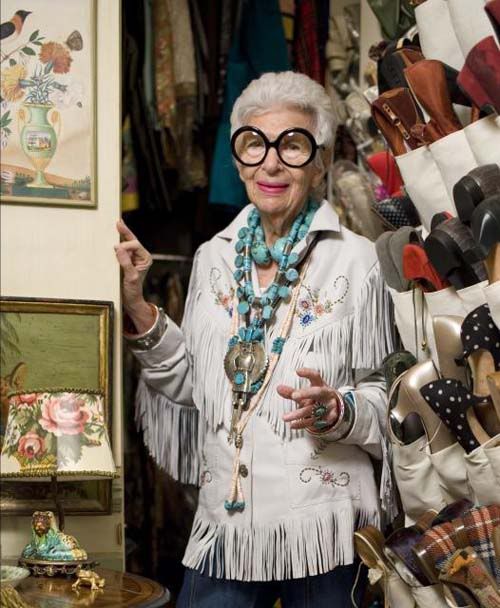

Iris Apfel (born Astoria, Queens, New York, 29 August 1921) is an American businesswoman, former interior designer, and fashion icon.

Born Iris Barrel, she was the only child of Samuel Barrel (born 1897), whose family owned a glass and mirror business, and his Russian-born wife, Sadye (aka Syd), who owned a fashion boutique.

She studied art history at New York University and attended art school at the University of Wisconsin. As a young woman Barrel worked for Women's Wear Daily and for interior designer Elinor Johnson. She also was an assistant to illustrator Robert Goodman.

In 1948 she married Carl Apfel. Two years later they launched the textile firm Old World Weavers and ran it until they retired in 1992. During this time, Iris Apfel took part in many design restoration projects, including work at the White House for nine presidents: Truman, Eisenhower, Nixon, Kennedy, Johnson, Carter, Reagan, and Clinton.

In 1948 she married Carl Apfel. Two years later they launched the textile firm Old World Weavers and ran it until they retired in 1992. During this time, Iris Apfel took part in many design restoration projects, including work at the White House for nine presidents: Truman, Eisenhower, Nixon, Kennedy, Johnson, Carter, Reagan, and Clinton.Iris Apfel still consults, and also lectures about style and other fashion topics. She calls herself a 'geriatric starlet' but she's fashion's latest muse, inspiring everyone from designers to glossy magazine editors. Iris Apfel talks to Gaby Wood about a lifetime's obsession with dressing up – and why she'd never spend more than $15 on a pair of jeans

In 2005, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City premiered an exhibition about the fashionable style of Iris Apfel entitled Rara Avis (Rare Bird): The Irreverent Iris Apfel. The success of the exhibit was profound that planted the seed for traveling versions of the exhibit displayed at the Norton Museum of Art in West Palm Beach; the Nassau County Museum in Nassau County, New York; and the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Mass. The Museum of Lifestyle & Fashion History in Boynton Beach is in the conceptual phase of a 93,000 square feet (8,600 m2) new building that will include a dedicated gallery for the clothes, accessories and furnishings of Iris Apfel.

In 2005, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City premiered an exhibition about the fashionable style of Iris Apfel entitled Rara Avis (Rare Bird): The Irreverent Iris Apfel. The success of the exhibit was profound that planted the seed for traveling versions of the exhibit displayed at the Norton Museum of Art in West Palm Beach; the Nassau County Museum in Nassau County, New York; and the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Mass. The Museum of Lifestyle & Fashion History in Boynton Beach is in the conceptual phase of a 93,000 square feet (8,600 m2) new building that will include a dedicated gallery for the clothes, accessories and furnishings of Iris Apfel.Apfel is 88, a "geriatric starlet" (her own description) who has suddenly become a staple of hip New York life – photographed by Bruce Weber, admired by designers such as Isaac Mizrahi and Duro Olowu, featured in Paper magazine, Vogue and the New York Times, blown up beyond life-size in the window of Barneys department store. In the five years since a show of her clothes at the Metropolitan Museum's Costume Institute was a word-of-mouth sensation, she has taken the world of style by storm. Her looks are now so legendary, so otherworldly, that many who first saw the exhibition assumed she was dead. Her nephew made a habit of taking friends to see it, and she gave him strict instructions: "If you hear anyone say I'm dead, tell them: 'No, she's very much alive and just walking around to save funeral expenses.'"

Apfel thinks her sudden cult status is very funny. There she was, as she sees it, minding her own business. The Costume Institute wanted to borrow some of her accessories, and then they thought perhaps they should borrow some clothes to put them in context. "I said: 'Oh that's a great idea. What would you like?'" Apfel recalls. "They said: 'Well, we don't know. What have you got?' That opened the Pandora's box. They started to go through all the closets, all the armoires, all the drawers, all the boxes, things on top of the closets, under the bed… they kept dragging things out and oohing and ahhing. Before you know it, we had to push all the furniture to one side, and we had to buy 10 pipe racks to hang stuff."

A version of the show is now on view at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts, and some of the setups are so delirious they look as though they might have travelled directly from the mind of Luis Buñuel. A feather-clad mannequin sits astride an ostrich; an ensemble made to order entirely of leopard-print velvet (coat, skirt, boots, bag) is worn by a mannequin leading a leopard by a rope – the leopard is wearing Apfel's glasses. "There's a sad lack of glamour in the world today," Apfel mourns. "And there's absolutely no fantasy."

But Apfel is not just the queen of kookiness. Admittedly, she once wore a necklace made of plastic finds – a toy calculator, figurines, a chewing gum packet – and yes, she still fondly recalls a necklace which would have required at least two bearers to carry her, but she is not always a maximalist. One beautiful outfit combines a sleek orange Geoffrey Beene jumpsuit with chunks of turquoise turned into a belt. Another is a dress made in 1968 by James Galanos of ivory satin ribbons woven together. She is also unremittingly practical: Old World Weavers, the company she founded with her husband, Carl Apfel, was hired to restore the fabrics in the White House over the administrations of several presidents. She found that President Nixon never turned the heating up, so she wore a warm, heavy priest's tunic that she'd found in a flea market to formal dinners.

But Apfel is not just the queen of kookiness. Admittedly, she once wore a necklace made of plastic finds – a toy calculator, figurines, a chewing gum packet – and yes, she still fondly recalls a necklace which would have required at least two bearers to carry her, but she is not always a maximalist. One beautiful outfit combines a sleek orange Geoffrey Beene jumpsuit with chunks of turquoise turned into a belt. Another is a dress made in 1968 by James Galanos of ivory satin ribbons woven together. She is also unremittingly practical: Old World Weavers, the company she founded with her husband, Carl Apfel, was hired to restore the fabrics in the White House over the administrations of several presidents. She found that President Nixon never turned the heating up, so she wore a warm, heavy priest's tunic that she'd found in a flea market to formal dinners."Iris is more 'street' than anyone I know," says the British-Nigerian designer Duro Olowu, who has been friends with Apfel since they met at a fashion awards ceremony years ago. "You think of the great dressers – Gloria Guinness or Bab Paley – and there's a certain sense of sadness and sacrifice to them. It's immaculate but cold. Iris dresses how we'd all dress if we had the eye. Fashion is like a big box of Lego to her." Olowu says Apfel's show has been so influential that designers "go silent" when he says he knows her, but that really, its success can't be attributed merely to fashion. "It's not a trend," he says. "It appeals to a certain kind of joy in everybody."

Some people own such valuable clothing they would never dare to put it on. This is anathema to Apfel. There's one lady who lives in the Midwest who has about 15,000 pieces. She once wanted to show Apfel some of her collection, and when she took out "this divine Geoffrey Beene dress", Apfel said: "Oh my God, you must have had so much fun wearing it!" The woman was horrified. She said: "Wear it!? This is part of my collection. You don't wear your collection!" Apfel said: "In that case I don't have a collection."

The only reason Apfel has kept her show going is that she's had so much mail in response. "People say: 'You have inspired me, you've given me courage…' They've gone so far as to say you've changed my life! And I would come back and say to my husband: 'I can't understand it – what kind of poor little life did she have if I had to come and change it?'" Her husband said she should ask. And sure enough, the next time someone said she'd changed her life, the fan was a 70-year-old lady in Florida. Apfel thanked her, then took her aside and said: "Would you mind very much explaining that to me?" So the woman did. She said that she'd never wanted to look just like everybody else, but she wasn't sure how to do that without looking silly. Once she saw Apfel's show, she knew, and what's more, she said, "now that I've learned I don't have to look like everybody else, I don't have to think like everybody else".

The first time Iris, thought "I have nothing to wear!", she was eight years old. Her mother had arranged for her to have a formal portrait taken, and together with her nanny, the eight-year-old fashioned something Isadora Duncan-like out of cheesecloth. What followed was a lifetime of improvisation. The granddaughter of a Russian master tailor, she grew up in Queens. Her father was an eccentric decorator and her mother, who had a flair for tying scarves, made all the money. When Apfel was a child the legendary interior designer Elsie De Wolfe hired her father to install all the mirrorwork in some suites she was putting together at the Plaza Hotel. Apfel would visit her, and de Wolfe would receive the girl from her bed, wearing a dressing gown she'd had made to order out of mink.

The first time Iris, thought "I have nothing to wear!", she was eight years old. Her mother had arranged for her to have a formal portrait taken, and together with her nanny, the eight-year-old fashioned something Isadora Duncan-like out of cheesecloth. What followed was a lifetime of improvisation. The granddaughter of a Russian master tailor, she grew up in Queens. Her father was an eccentric decorator and her mother, who had a flair for tying scarves, made all the money. When Apfel was a child the legendary interior designer Elsie De Wolfe hired her father to install all the mirrorwork in some suites she was putting together at the Plaza Hotel. Apfel would visit her, and de Wolfe would receive the girl from her bed, wearing a dressing gown she'd had made to order out of mink. Apfel tried her hand at teaching – she got a degree in education – but she was sent to a one-room schoolhouse in rural Wisconsin, which was overseen by a large lady with a shotgun across her lap. Nothing could have been further from the Plaza, and before long Apfel had skipped out, befriended Duke Ellington ("Lordy, Lordy, who's your tailor?" asked his band leader Ray Nance when he saw Iris in slacks at the stage door) and become a decorator herself. It was wartime, and she'd known the Depression; Apfel's style rarely departed from the ingenuity forced by affordability, and the ingenuity remained, however rich her clients became. Or indeed, however rich she became, though the facts of that are rather harder to discern. When I ask Apfel at what point she came into money she looks a little bemused and says: "Money? Oh, I'm not rich." This, spoken beside historical art masterpieces in a Park Avenue apartment. But it's all relative, I suppose. And wealth is in many ways a state of mind. Apfel asserts that she would never spend $700 on a handbag – not because she doesn't have $700 to spend, but because she doesn't think handbags should cost that much. Incidentally, she votes Republican. She is socially liberal, she explains, but fiscally conservative.

Apfel tried her hand at teaching – she got a degree in education – but she was sent to a one-room schoolhouse in rural Wisconsin, which was overseen by a large lady with a shotgun across her lap. Nothing could have been further from the Plaza, and before long Apfel had skipped out, befriended Duke Ellington ("Lordy, Lordy, who's your tailor?" asked his band leader Ray Nance when he saw Iris in slacks at the stage door) and become a decorator herself. It was wartime, and she'd known the Depression; Apfel's style rarely departed from the ingenuity forced by affordability, and the ingenuity remained, however rich her clients became. Or indeed, however rich she became, though the facts of that are rather harder to discern. When I ask Apfel at what point she came into money she looks a little bemused and says: "Money? Oh, I'm not rich." This, spoken beside historical art masterpieces in a Park Avenue apartment. But it's all relative, I suppose. And wealth is in many ways a state of mind. Apfel asserts that she would never spend $700 on a handbag – not because she doesn't have $700 to spend, but because she doesn't think handbags should cost that much. Incidentally, she votes Republican. She is socially liberal, she explains, but fiscally conservative. She met Carl Apfel on holiday at a hotel. He told a mutual friend that she'd be very attractive if she'd only get her nose fixed. Iris said: "Well, you can tell him what to do!" They've been married now for almost 62 years. They've been so busy, working and travelling and collecting and speeding in the Maserati that, for one thing, they "haven't had time" for children. "We did have the good fortune to see the end of the old world," says Apfel, and images of the couple wearing evening clothes on transatlantic steamers and sunning themselves on Capri come effortlessly to mind. "In my view," she says, "you can't go to the future if you haven't come from the past."

She met Carl Apfel on holiday at a hotel. He told a mutual friend that she'd be very attractive if she'd only get her nose fixed. Iris said: "Well, you can tell him what to do!" They've been married now for almost 62 years. They've been so busy, working and travelling and collecting and speeding in the Maserati that, for one thing, they "haven't had time" for children. "We did have the good fortune to see the end of the old world," says Apfel, and images of the couple wearing evening clothes on transatlantic steamers and sunning themselves on Capri come effortlessly to mind. "In my view," she says, "you can't go to the future if you haven't come from the past."In the old days, you could go to Tunisia and get jeans directly from the people who were making them for Pierre Cardin. You could really find things in souks and flea markets. "Now they're all picked over," Apfel says, "and everybody thinks they know something." And if you couldn't afford couture, you could go to the fashion houses before anyone cared about archives, and buy their one-off samples. As a result, Apfel has a wardrobe literally unlike any other in the world. "Valentino cut for much smaller women," says the tiny Apfel, "but Dior, Ricci, Lanvin, Jean-Louis Scherrer…" Apfel reaches back wistfully. "I was never a fan of Chanel. I liked it on other people. Some other people. All the ladies who were too plump and busty looked like little sausages."

There's a wonderful drawl to Apfel's speech, which has less to do with any particular accent than with timing; she'll say something you think is surprising, and by the time her voice has finished with it, you've just about caught up with its self-evidence. Her wit dries out slowly.

There's a wonderful drawl to Apfel's speech, which has less to do with any particular accent than with timing; she'll say something you think is surprising, and by the time her voice has finished with it, you've just about caught up with its self-evidence. Her wit dries out slowly.Despite her fondness for rare sartorial finds, there was a phase in the early 50s when she "never got dressed", as she puts it. "I had one very bad experience," Apfel remembers. "As a decorator, I was dealing with all these shallow, silly women. Lots of them used to congregate in the showroom after a day of shopping. I had some doctors' wives, and one day one of them was wearing some beautiful alligator pumps. One of the ladies said: 'Oh my goodness, those are great-looking.' She said: 'Oh yes, two heart attacks.'" A couple of people had had to die, or almost die, in her husband's arms for those shoes. "So I took to wearing a black tunic with black stockings, high black boots, a hood. It was like a revolt."

But then she came face to face with the problem she'd experienced as an eight-year-old all over again. "I had to go to a series of parties. And I couldn't find anything. Balenciaga had done a few prêt things. It was obscene; it was like 300 and something dollars, which would be like $10,000 now. But I was just desperate." Apfel, who was in the habit of waiting for "a million markdowns" and still doesn't like to spend more than $15 on a pair of jeans, was forced to shell out wads of cash. "And what really killed me was they charged me $35 to do a hem! And I said to myself: I will never, ever let myself get into this shape again."

That was the moment when Apfel's free spirit began to accumulate full outfits. Her theory about women's fashion is that its conventions and limitations are dictated by women's insecurities. Apfel doesn't feel constrained by her physique. She doesn't think one should reveal one's upper arms after a certain age, and she doesn't much like girly, chiffony dresses, but the fact is, she is 88, has never had any plastic surgery and she dresses like a wonderfully inventive child-queen.

That was the moment when Apfel's free spirit began to accumulate full outfits. Her theory about women's fashion is that its conventions and limitations are dictated by women's insecurities. Apfel doesn't feel constrained by her physique. She doesn't think one should reveal one's upper arms after a certain age, and she doesn't much like girly, chiffony dresses, but the fact is, she is 88, has never had any plastic surgery and she dresses like a wonderfully inventive child-queen.The days when she felt insecure are long gone. "You learn as you grow up, if you're intelligent – or even three-quarter witted – that there's no free lunch. You pay for things in various ways. Living, loving, everything else is a matter of the same principles: you learn to work with what you have. And there's nobody today who can't do something to help herself."

What's more, being unconventional has had lasting benefits. "If you can't be pretty, you have to learn to make yourself attractive. I found that all the pretty girls I went to high school with came to middle age as frumps, because they just got by with their pretty faces, so they never developed anything. They never learned how to be interesting. But if you are bereft of certain things, you have to make up for them in certain ways. Don't you think?"

I suspect Apfel has become a more intriguing proposition with age and white hair, as if she and her clothes have evolved into an entirely new species – a "rare bird of fashion", as the title of her book has it. And while she has advice to give if you ask for it, she recognises that not everyone can carry off such wonders as have erupted from her mind. "Doing your own thing is very good," Apfel concludes, "if you have a thing to do."

I suspect Apfel has become a more intriguing proposition with age and white hair, as if she and her clothes have evolved into an entirely new species – a "rare bird of fashion", as the title of her book has it. And while she has advice to give if you ask for it, she recognises that not everyone can carry off such wonders as have erupted from her mind. "Doing your own thing is very good," Apfel concludes, "if you have a thing to do."

Carl and Iris Apfel have supported many charities including a $1.2 million donation to the University of Miami's Bascom Palmer Eye Institute

No comments:

Post a Comment